Protein Earrings

BackWhat You're Looking At

What you’re looking at are earrings whose design is derived from protein structure. You'll find a fuller description of the model below along with directions and technical overview.

Directions

In the control panel, use the buttons and sliders to change the model and display parameters. These are explained in the description section. The default protein is the crystal structure of sOPH, a hydrolase found in microbes shown to break down PVA plastics. However, you can search by title for any protein in the RCSB database to change the underlying structure.

As a starting point, try setting the “Smoothing Passes” parameter to 6. Then try changing the underlying structure. Type “jac” into the search bar and choose the first option from the dropdown menu.

Description

I took an architecture course at University of Chicago called “Complex Curves and Plastic Shapes,” which focused upon both theory and practice. The theory half of the course was devoted to reading and discussing essays on and by artists, primarily sculptors. In the practical half of the course, we tackled design assignments using Rhino, a 3D modeling software.

As the course went on, I became increasingly interested in both the practical and theoretical role of codes in art. On the theoretical side, many of the artists we studied made explicit reference to a set of rules endogenous to art, arguing that these should govern artmaking and our interpretation of art itself. (You can read an adaptation of an essay I authored here exploring in more depth the emergent properties of these rule sets when viewed as codified languages.)

On the practical side, I started to see parallels to what I was teaching myself in Grasshopper—a plugin for Rhino which provides a programming environment to create models and explore design variations through definable parameters.

This model and my final paper for that course at UChicago were catalyzed by another happy edge effect. Sprinkles of two concurrent courses—Multiscale Biological Modeling and Spanish—evoked ideas that mingled in my imagination to get me thinking of proteins in totally different contexts, the linguistic and the sculptural.

There is actually a quick leap from proteins to language. Akin to sequences of characters in a language, nearly every protein comprises some combination of the same 22 proteinogenic amino acids. The analogy extends to scales both smaller and larger than that of amino acids. Each amino acid within a protein is encoded, with some redundancy, by one out of 64 possible three letter sequences of nucleotides (A, G, C and T), fittingly known as codons. For that reason, DNA is often referred to as the “language of life.” Across every scale, there is a readily definable vocabulary of building blocks which combine according to a grammatical structure. When it comes to proteins, biochemists generally refer to four structural scales: primary structure is specified by the amino acid sequence; secondary structures are local spatial conformations (α-helices, β-sheets, turns); tertiary structure describes how an entire protein folds into a 3-dimensional shape; quaternary structure is the spatial association with different proteins.

These organizational rules govern and give rise to an object whose function is intimately tied to form. Celebrated artists such as Katarzyna Kobro, Georges Vantongerloo, and Barbara Hepworth might argue over the specifics, but all understood artistic form as a product of a language-forming rule set.

The Protien Earrings project is therefore an exploration into the ways that following—and breaking—codes inform artmaking. Breaking the connection between a form and its underpinning code is sometimes the best method of proving the connection exists. In biology, this happens naturally through transcriptional errors, misfolding, or denaturing, all of which divorce a protein’s form from its underlying code. To study protein function and dysfunction, biologists often recreate these breaking conditions.

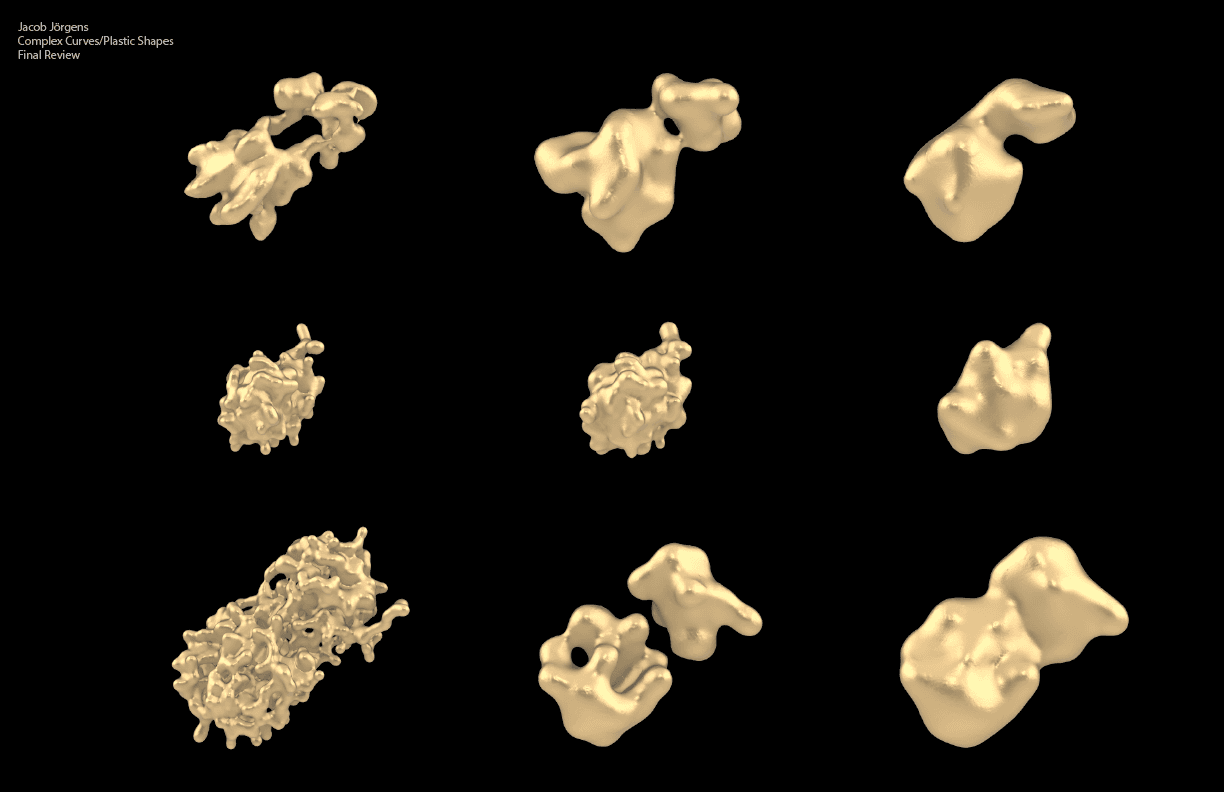

Here is a figure I generated to capture and compare 9 instances of this language in use, with three different protein structures pronounced over three distinct parameter sets:

My model is designed to break the protein’s form-code connection not by mimicking actual biological processes but by introducing a new visual vocabulary and grammatical structure. To create these earrings, I deliberately disrupted the well-established three-dimensional language by using a new rule-based system. My goal was to gain a deeper, more empathetic understanding of the role of linguistics in art, as described by Kobro, Vantongerloo, and Hepworth.

At each atom position the model receives from input, it places a metaball point charge (essentially a sphere that can meld with others at close proximity), generating the base vocabulary of my new rule-based system. The radius parameter changes the size of the spheres and the remaining inputs together form a grammar which governs the combination of these sculptural components. Parameterization allows the user to play with the resulting sculptural language and participate in the creative process.

Trim Tolerance:

Proteins are made of thousands of atoms which are, by definition, very close to one another. The model imposes a rule to trim neighboring atoms from the input data that fall within a certain distance. This parameter sets the distance or tolerance used to filter out neighbors. A higher value trims a greater number of atoms from the input data and a lower value maintains a greater number of atoms.

Charge Strength:

Charge strength determines the distance over which metaball charges interact. A higher value means that metaballs will meld into a single, contiguous object at greater distances. A lower value will preserve the spherical shape of metaballs in closer proximity.

Smoothing Passes:

The metaball point charges are wrapped in marching cubes to create a mesh. This parameter sets the number of times to run the Laplacian smoothing algorithm on polygonal meshes. A higher value yields a smoother object. A lower value preserves more of the topological features that come from the metaball charges.

Scale:

Changes the size of the earring hook

There are other, hidden parameters that also feed into the model’s grammatical structure. I’ve decided not to include these in the user interface for a few different reasons. The first is to try to limit artifacts. Similar to what can happen in real protein synthesis, the grammatical structure of this model is blind to input. Whereas in nature, genetic mutations might yield protein variants that take on new, unexpected functions possibly associated with disease, this model’s grammar will output mutant forms (e.g. 2D shards, disjoint volumes) if fed a particular mix of inputs. I can’t calculate which of the hundreds of thousands of possible inputs will generate artifacts but I have constrained certain value ranges and filtered out everything but the largest mesh to avoid generating artifacts. The second reason I decided to limit user-facing parameters was to keep things simple. There is quite a lot to take in as it is and the parameter space already provides a dizzying number of possible combinations to explore. The third reason was to keep things running quickly. Some of these algorithms (marching cubes and mesh refinement in particular) can become remarkably expensive from a computational standpoint. To keep the language fluent, I decided to hide parameters that might cost more than a second.

How It Works

Input data is sent to a Grasshopper file which is passed to a Rhino.Compute server hosted on an AWS EC2 instance. The Rhino compute server returns rhino3dm JSON data which is loaded and rendered in the browser using Three.js. There are three categories of input data: 1) parameter values, 2) display values and 3) pdb atom data. Parameter and display values are both set in the graphical user interface. Changes to display values only trigger re-renders in the browser because they only involve Three.js. All other changes trigger calls to the Rhino.Compute Server to run the grasshopper file with updated parameters. When the page loads and all the components mount, the Rhino.Compute server is called with a default protein, in this case an enzyme found to break down PVA plastics. This default PDB data can be changed from the search bar which queries the RCSB Protein Data Bank API.